Librarians have been debating the value and worth of comics for a while now. Back when comics were first starting out in the 1920’s, we didn’t like them. How much we didn’t like them depended on whether we thought comics were merely a waste of children’s time and taking time away from more quality literature, or if we thought they were actually hurting children with the use of violent imagery and vulgar language. Either way libraries most certainly wouldn’t be collecting such “trash.” Comics were maligned and ignored for so long that even in 2003’ Hammond stated that "graphic novels hadn't created a blip on my radar screen." In 2003, she was probably in the minority of librarians unaware of the format, but this is just an example of the hurdles comics must still overcome to gain recognition as a useful mode of imparting complex ideas.

Thankfully, librarians and comics have a come a long way since then. However, that negative image has been hard for comics to shed, even as more and more librarians accepted and even embraced them, parents are often hesitant to see comics and graphic novels as anything more than lesser reading material. Even though Hammond extols the virtues of multimodal literacies gained through reading graphic novels, she still seems stuck in the idea that superhero comics and manga aren’t of the same literary quality as “art graphic novels.” While that may be true in some cases, there must be some way to extol the virtues of “art graphic novels” without tearing down superhero comics and manga. If introducing youth to the multimodal literacies of comics is the goal, why shouldn’t superheroes and manga be considered just as useful?

Maliszewski provides a more balanced look at the school library graphic novel collection. She encourages librarians to collect works that are popular in addition to works with merit. Her problem arises when she tries to nail down a graphic novel canon for younger children. Admittedly comics aimed at younger children don’t have as extensive a history as comics aimed at teens and young adults, but I think she missed out on mentioning the Eisner Award winners in the Kids and Younger Reader’s sections, which reach back to 1996. Even in the last four years there has been an ever increasing boom of great comics for kids. Snarked by Roger Langridge won the 2012 Eisner Award for best publication for kids. The story is based around characters from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass. It succeeds with plenty of adventure, royalty, and humor added to its cartoony, but detailed art.

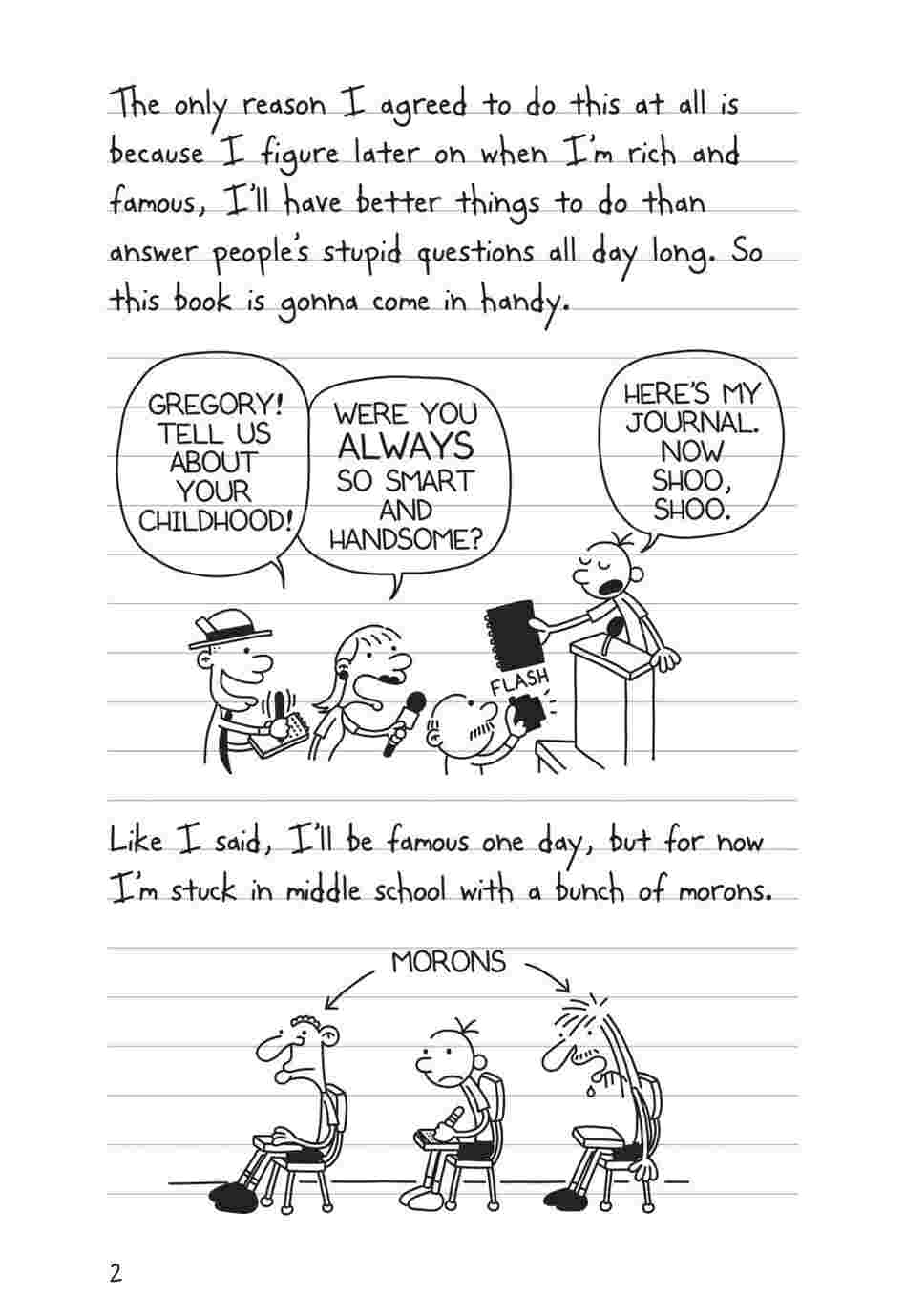

As for popularity, the big trend of illustrated diary fiction (Diary of a Wimpy Kid, Dork Diaries, Big Nate being just a few examples) is often excluded from discussions of graphic novels. If we go by McCloud’s definition “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer,” then these books are indeed comics.

While each illustrated panel is often separated by a paragraph or two of text, the text itself is designed to both convey information, while also evoking an aesthetic response from the viewer that this book is in fact a real diary from a real kid. Any thoughts on why these sorts of comics don’t get talked about more often?

Morgan- I agree with your assessment of Maliszewski's idea of canon in kid and young adult graphic novels. Like you mentioned with the Eisner award, I feel as though she passed up a lot of great resources to find great graphic novels for kids.

ReplyDeleteI think you're right on spot with your statement that a diary format shows the reader a 'real' diary of a 'real' kid. I haven't read any graphic novels in a diary format, but I have read a lot of autbiographical GN, which are very similar in a lot of ways. For example, Smile by Raina Telgemeier is in Telgemeier's voice and headspace. It doesn't have the blocks of text, but it is a very talky graphic novel.

As for why there isn't more talk about these genres, I don't know. Possibly, it's because people see the diary format as "lower literature" and don't give it the credit it is due.

-Virginia (Ginny)

Morgan:

ReplyDeleteThe Diary Fiction, such as the Wimpy Kid, has been questioned by comic book lovers since its introduction in 2004. It got a lot of attention online first as a quasi-web comic, which didn't help it to begin with. Just as librarians seem strict at times about where a book goes in the catalog or shelves, in the early 2000s the Comic Book Literati, as I like to refer to them, were not too hip on 1. web comics, and 2. novels with pictures that tried to be comics. When I say "tried to be comics" I simply mean that to the CBL it seemed that publishers were making an effort to market them to the CBL readers to have a bigger readership rather than the book actually being produced for them. That rubs us the wrong way. To the CBL the popularity of comics should rise from below, not come down from on high. We as a group decide, not the publishers. At least that’s what we would like.

Is Wimpy Kid a comic or graphic novel? Well, where is it shelved in the library?

If we use McCloud’s definition, it’s important to focus on “intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer.” It clearly is to produce an aesthetic response, but are the images used (at least in your example) positioned so that the transition between the images convey information? Arguably, perhaps. But not clearly. McCloud’s definition is focused on the images, not the text. He doesn’t ignore it, but a comic has to have pictures. Thus, the definition is about images. There doesn’t have to be frames or panels, and it’s not because there is more verbal than visual, and there are probably excerpts from the books that are in fact sequential art. But the book as a whole? I don’t think many would argue that the Wimpy Kid books are not fiction or even a novel – even if only a YA novel. And while there may be no true answer here, as a whole, it is simply not a comic book or graphic novel.

-Mike